The State of the Onion 9

For the last couple of years, we’ve been homeschooling our two youngest kids. Gloria has been making sure they learn the easy subjects like history and mathematics. I’ve been making sure they also learn the hard subjects like, um, cinematography. So I’ve been making sure they view some of the great classics.

James Bond materials copyright 1962 - 2005 United Artists Corporation and Danjac, LLC

Home schooling works best if the parents learn alongside the children, so I’ve been forced to watch the Bond corpus along with my kids.

Or is that the Bond corpses? Seems like there are an awful lot of them.

Anyway, it’s a large body of work.

Though some of the bodies are larger than others. If you know what I mean, and I think you do.

Anyway, now that I’ve been wading through the Bond corpus again, I’ve noticed something I’ve never noticed before about the show. It’s just not terribly realistic. I mean, come on, who would ever name an organization “SPECTRE?” Good names are important, especially for bad guys. A name like SPECTRE is just too obvious. SPECTRE. Boo! Whooo!! Run away.

You know, if I were going to name an evil programming language, I certainly wouldn’t name it after a snake. Python! Run away, run away.

When I was young I actually preferred Man from U.N.C.L.E.

Now “THRUSH,” that’s is a decent name for an evil organization.

Oh, and then there’s Get Smart.

Unlike James Bond, it’s highly realistic. I can believe in an evil organization with a name like “KAOS.” After we’re done with the James Bond series, I plan to show my kids Get Smart. I want to make sure my kids score high on intelligence tests. Ba dump bump.

I’m a child of the Cold War. We didn’t go quite as far as to build a bomb shelter, but we actually thought about it before deciding our house would probably burn up anyway. Back then people thought you could win a nuclear war, or at least try real hard not to lose one. Eventually we all figured out that imperfect knowledge was a feature, and so we settled on a national policy of Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt, though they couldn’t bring themselves to call it the FUD doctrine, so they called it MAD instead. Probably because they read too much MAD magazine. Hmm, that puts a whole new twist on the “Spy vs. Spy” comics.

Anyway, as a child of the Cold War, I know that seeing a mushroom cloud is a good thing, since it means you haven’t been vaporized just yet. Sort of the same principle that you should never be scared of thunder, since the shocking part is already over with. Or more subtly, if you live under the flight path of several airports, like me, you’re always wondering if the Blue Angels going 100 feet overhead are going to run into your house. But as soon as you hear the Doppler shift dropping in pitch, you know that they’re probably going to miss your house, because if they were on a collision course with your house, the pitch would stay the same until impact. As I said, that’s one’s subtle.

Of course, you should also plan ahead. Where there’s one plane, there’s likely to be another one coming along after it. And lightning does strike twice in the same place. And, if you see a mushroom cloud, I would suggest that you start replanning your short-term future. And your new future plans should probably take into account not only your future but the future plans of about a million other people who just saw the same mushroom cloud and are suddenly replanning their futures.

Anyway, planning is good. Well, some planning.

Everyone my age and older knows that Five-Year Plans are bad for people, unless of course you’re someone like Josef Stalin, in which case they’re just bad for other people. All good Americans know that good plans come in four-year increments, because they mostly involve planning to get reelected.

I probably shouldn’t point this out, but we’ve been planning Perl 6 for five years now.

Comrades, here in the People’s Republic, the last five years have seen great progress in the science of computer programming. In the next five years, we will not starve nearly so many programmers, except for those we are starving on purpose, and those who will starve accidentally. Comrades, our new five-year mission is to boldly go where no man has gone before! Oh wait, wrong TV show.

You might say that Perl grew out of the Cold War. I’ve often told the story about how Perl was invented at a secret lab that was working on a secret NSA project, so I won’t repeat that here, since it’s no secret. Some of you have heard the part about my looking for a good name for Perl, and scanning through /usr/dict/words for every three- and four-letter word with positive connotations. Though offhand, I can’t explain how I missed seeing Ruby. So anyway, I ended up with “Pearl” instead.

But it’s a little known fact that one of the three-letter names I considered for quite a while was the word “spy.” Now, those of you who took in Damian’s session on Presentation Aikido are now wondering whether I’m just making this up to make this speech more interesting. And in this particular case, I’m not. You can ask my brother-in-law, who was there. On the other hand, please don’t ask him to vouch for anything else in this speech.

But wouldn’t “Spy” be a great name to give to a language whose purpose was pattern matching and reporting? Hmm. And spies are also called “agents of change.” “Practical extractions are one of our specialties.”

Instead of a warn operator, it’d have to be the warn off operator. Instead of having a die operator, we might have had the let die operator. Then we’d get Perl poetry, I mean, Spy poetry, with phrases like live or let die.

How history might have been different! Those of you who are Perl programmers might instead be attending the 9th annual Spy conference. And maybe Ruby would not have been named Ruby, but instead have been named Spook, or Agent. And Python might not have been named after Monty Python, but after some other comedy troupe. It might be called Stooge, or Muppet, or something.

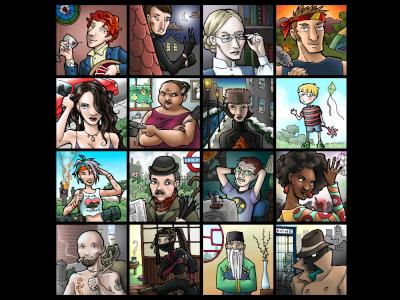

Even if you’re not a child of the Cold War, you’ve been affected. My kids have been affected. Lately my son Aron and my daughter Geneva have been designing a game. No, not a computer game. It’s a kind of a board game involving spies and cool gadgets. It’s not done yet, so don’t pester them over when it’s going to be done. At least, don’t pester them any more than you pester me about Perl 6. Heh, heh.

But as soon as I saw their cast of characters, I knew I had my theme for this year’s talk. For some reason, any time I see a really diverse set of characters, I think of the open source community in general, and the Perl community in specific.

So if you’re new to the department, I’d like to introduce you to a few of the other spooks working for the organization.

The cards for this game list various stats for each character’s strengths and weaknesses, as well as their favorite gadget. Now, as it happens, these spies all happen to be Perl programmers as well, so in this talk maybe we’ll get to see what their favorite Perl gadgets are.

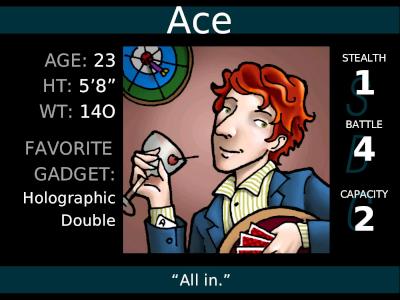

Ace is the quintessential spy. All the fake spies like James Bond are based on him. And like Bond, Ace is such a good spy that he doesn’t care if everyone knows he’s a spy. Ace knows he’s the hero of the story, and therefore invincible.

So Ace does spying simply because it’s fun. That’s also why he does Perl programming. He knows it’s all just a big game, and it’s fun to win with the hand you are dealt. On the other hand, it’s also fun to win by changing the rules. It’s especially fun if you can win using someone else’s money.

You know, when you think about it, most open source software is written using someone else’s money. Most Perl programmers are not paid directly to hack on Perl, or Pugs, or on CPAN modules. A lucky few are paid to have fun, but most of us have to make a living some other way, and our bosses kindly let us spend part of our time working on things that are mutually beneficial to the organization and to the world in general. And if we have fun doing that, they don’t seem to mind.

But on the flip side, the Aces of the world all seem to know how to create fun wherever they go, or at least they know how to go places where people know how to have fun. For this reason, Ace is one of the most important people in the Perl community.

This last year, we were starting to lose our sense of fun in the Perl community. Though we tried to be careful about not making promises, everyone knew in their hearts that five years is an awfully long time to wait for anything. People were getting tired and discouraged and a little bit dreary.

Then Autrijus Tang showed up. Maybe we should call him “Ace” Tang. He basically said, “Look, we’ll never get this done unless we optimize for fun.” So fun is exactly what the Pugs project is optimized for. Mind you, Autrijus’s idea of fun is to learn Haskell and then write a prototype of Perl 6 in it. Now, for those of you who don’t know, Haskell is one of those pure functional languages that doesn’t allow any side effects (except, of course, when it does). Really way-out-there stuff, compared to the thinking of the average Perl programmer.

Furthermore, Autrijus thinks it’s fun to persuade other functional programmers that it would fun to bootstrap Perl 6 in Haskell. These folks proudly call themselves the “lambdacamels.”

But when this happened, a few skeptical people in the Perl community thought they knew what was going to happen next. The cabal would say that this was just too crazy, and we already had Parrot, and why duplicate effort. You know, your basic turf-protection reaction.

But that’s not what happened. Instead, the cabal said, “Yay. We can work this problem from both ends now. Let’s give Autrijus all the help we can. Parrot will work bottom-up, and Pugs will work top-down.”

Did I say “work”? I meant “play.” That’s what Ace does best.

But not everyone is an Ace. Some people are naturally sneaky. Every organization needs a second-story man, and people like The Cat prefer to have their fun in private. I strongly suspect certain Perl programmers of being retired jewel thieves. You watch the version tree, and things mysteriously disappear in one place and appear somewhere else. Like a real cat, Le Chat’s ego is not involved in any kind of public way. That’s not to say that cats don’t have egos–just that they don’t care whether you notice.

Cats know how to get into and out of places they’re not supposed to be able to get into and out of. Cats seem to know how to levitate, and to pass through supposedly impermeable barriers. Even the stupidest cat knows how to make you think they’re reading your mind, but it’s all a trick.

In Perl culture, Cats also do sneaky things. Sneakiness is a good quality when you’re playing Perl golf, for example. Sneaky Perl programmers like to do sneaky things with overloading and with source filters. In fact, Le Chat is looking forward with glee to the day he can change the Perl 6 grammar on the fly and write yet another set of ACME modules. Oh, hi Damian–didn’t see you there.

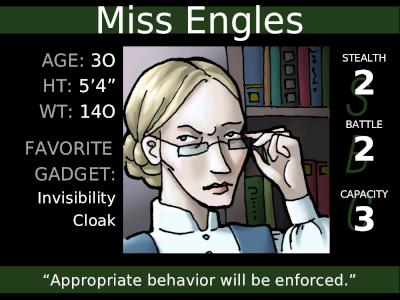

This is Miss Engles. She’s a librarian. Like a jewel thief, she also moves things from place to place, but for very different reasons. A jewel thief moves things from where they belong, while a librarian moves things to where they belong. A place for everything, and everything in its place. Miss Engles likes those aspects of Perl 6 that support literate programming, and that let her index the documentation in various ways.

Miss Engles has never cracked a smile because, oddly enough, not cracking a smile is what makes her happy. She is a librarian all the way to the bone. Or that’s what she’d like you to believe.

But in fact, as we all know from the movies, librarians take off their glasses and let down their hair when they get off work, and become completely different people. Librarians instinctively understand paradigm shifts, having perused most of the history section in their spare time, not to mention a great deal of the psychology section. So nothing ever surprises a librarian, least of all themselves. If a librarian ever says “I’m shocked,” you know they’re being completely sarcastic.

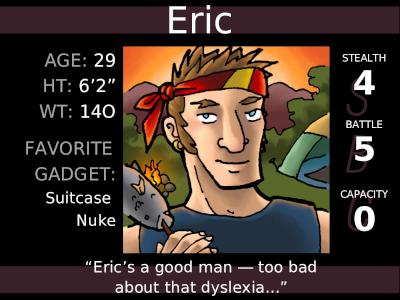

Eric has a problem with dyslexia, so he’s never going to be a librarian. But that’s okay, since he’s not terribly interested in the things librarians are interested in. Now, since Miss Engles is officially interested in almost everything, that makes it a little tough for people like Eric, since it forces him to be interested in almost nothing. But that’s okay–give him a fishing pole and a tent, and he’s happy. Oh, he wouldn’t mind a suitcase nuke, either.

Perl culture is full of easy-going, straightforward people. Actually, now that I look at it, this looks like Eric O’Reilly, long-lost cousin to Tim O’Reilly. Just kidding. But Tim has always been a straight dealer, and so is Eric, in his own way. I think with Tim it’s a matter of choice, but with Eric–well, that’s just the way he is.

Eric is the sort of agent you send skiing over the mountain to count enemy soldiers. Pick your term: he’s a trooper, or a SEAL, or a Marine. You know he’ll almost certainly come back alive, eventually, but you don’t quite know in advance whether he’ll have to kill all the enemy soldiers in order to count them. What you do know is that if he does, he certainly won’t hold it against any of them. Nothing personal. That’s just the way it is.

And when he reports in, you’ll just get the facts, without much interpretation. Eric doesn’t put many comments in his code. He thinks that if you have to comment a piece of code, you haven’t written it clearly enough. He is looking forward to working in Perl 6 because a lot of the magical cruft has been cleaned out of the language, or at least moved into places where he doesn’t have to worry about it, such as function signatures.

But the thing he loves most about Perl 6 is the multimethod dispatch, precisely because those crufty signatures also allow him to say what he wants without extra words.

Jezebel isn’t really a bad girl. She’s just drawn that way.

For all we know, this might be Miss Engles on her day off.

That being said, I wouldn’t mind it if there more female programmers, especially female Perl programmers. And no, I don’t mean it like that, or my wife wouldn’t let me say it. But I think we need some spies to tell us what things in our culture appeal to women, and what don’t. And it kinda goes without saying that these spies need to be women. Well, look, the guys all have a lot of great ideas, but you know, guys tend to be rather, well, idea-oriented. In theory, Perl culture is supposed to be more cooperative than competitive, but it’s kind of hard to argue for that viewpoint when the vast majority of us are standing and pounding our chests like big gorillas. I include myself in that category. Er, the gorilla category, not the Jezebel category. Just thought I’d clear that up.

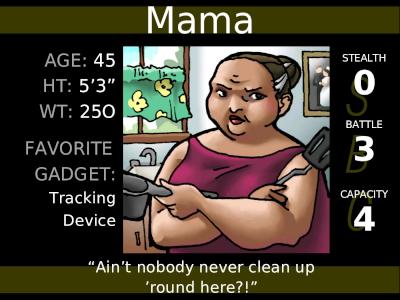

I think Mama represents the older generation of Perl programmers. Mama is wise to all the stupid tricks of the young’uns, and not afraid to tell ‘em off for it. Mama tends to be strict, but she has good reasons for it, because she takes the long view.

A lot of Mamas must hang out on PerlMonks–they’re the ones who are always saying “use strict; use warnings;” or you’ll grow up to be sorry you didn’t. And wipe your feet when you come in.

Mama kinda likes the fact that Perl 6 is growing up to become a strict language by default, but she isn’t quite sure what she’s gonna do after the kids are all grown up. It makes her happy and sad at the same time.

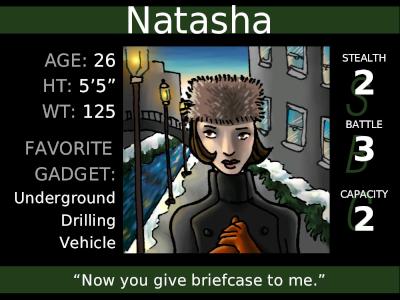

Natasha gets to represent the next wave of international programmers, particularly those from developing countries. Natasha’s mother probably worked for a large eastern-bloc TLA, and I don’t mean IBM. But Natasha is actually doing a bit of industrial work here. All in the interests of capitalism, of course. Though whose capital is perhaps a bit unclear at times.

A lot of people like Natasha are trying to figure out how to make a living in the new economic realities, and one of those economic realities is that the traditional western powers are trying to vacuum up all intellectual property rights on behalf of various corporate interests. And she wonders, rightfully so, if there will ever be any place in that economy for her, and for people like her.

So when our friend “Mad Dog” comes to town, and preaches the gospel that free and open source software is the only path to freedom, the only way for the rest of the world to push back–well, she can see the appeal of that notion.

And there are a lot of Natashas in the world, and potential Natashas. Over the long haul, she may well be the most important member of this list.

Oliver represents the next generation of programmers, who don’t even know it yet. Oliver is not ready to learn computer science. He is just starting to think about programming because he’d like to be a video game designer someday. He doesn’t know that what he likes best about Perl is that it will let him learn what he needs to know one concept at a time, without forcing him to learn a bunch of abstract concepts all at once before he really needs them. When he drives on the freeway, he drives in the slow lane.

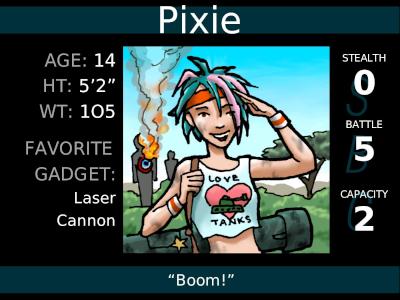

On the other hand, Pixie drives in the fast lane. She is what you might call an extreme programmer.

As an extreme programmer, Pixie loves testing. Preferably testing to destruction. The best defense is a good offense. She’ll get the job done, but she’s determined to have a lot of fun doing it.

Pixie works well in small teams, especially with pair programming. A team of two is the perfect size for her because wherever she’s aiming, her partner can always stand on the opposite side of her.

As part of a rapid response unit, Pixie is very much into rapid prototyping. So Pixie’s favorite Perl 6 feature is the yadayadayada operator, which lets her stub out new functions and blow up their interfaces even before the function bodies are written.

As the quintessential English banker, Mr. Radcliffe is a firm believer in reliability, with a dash of style. For our talk today, he gets to represent the business interests surrounding open source software. Mr. Radcliffe knows that businesses have different set of goals than most open source programmers, but he also knows that there is a great deal of overlap in those goals, and that the clever businessman can exploit that overlap to the betterment of both business and programmer.

You see, Mr. Radcliffe understands that one thing can have multiple functions. His umbrella is almost certainly multifunctional. Mr. Radcliffe’s favorite part of Perl 6 is that nearly every feature is multifunctional, though not completely orthogonal. That doesn’t bother Mr. Radcliffe, because nobody who rides cabs around in London expects complete orthogonality. He just expects to get where he’s going.

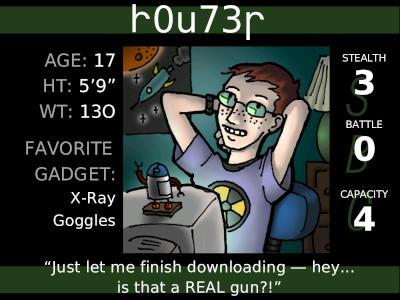

What can I say? Perl is also used by script kiddies. We just hope Oliver doesn’t grow up to be a script kiddie like r0u73r. Or if he does, we hope it’s just a passing phase.

And in fact, r0u73r used to be a script kiddie, but now uses his 1337 skills for good. To some extent, most of us were cargo culters as we learned how to program. We were reusing code, which is good, but we just didn’t always understand why we were reusing the code. But the Perl community has always had a soft spot for cargo culters, and seeks to educate them until they learn the real reasons for things being the way they are. Then they’re ready to join the real cult. Er, I mean, the real culture.

Anyway, as a vestige of his former ways, r0u73r looks forward to using the introspection capabilities of Perl 6, particularly when he can introspect someone else’s data structures.

Tina seems like a girl who just wants to have fun, but she’s really aspiring to be Mata Hari, except for the part about getting caught and executed. As a dancer, and perhaps an actress someday, Tina understands about playing roles. She knows that the role she’s currently playing is not who she really is. In Perl 6 terms, she understands the difference between an “isa” relationship and a “does” relationship. So she’s very much into the Perl 6 concepts of roles, traits, properties, and mixins.

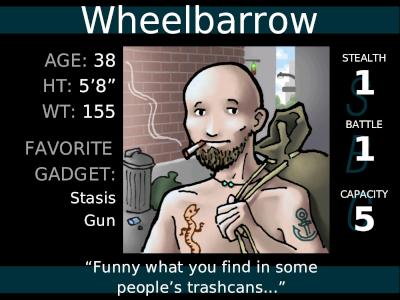

Wheelbarrow is a scavenger. That is to say, he’s a sysadmin.

Wheelbarrow loves to sift through the trash, which in his case consists primarily of discarded HTTP logs. Wheelbarrow loves the strong pattern-matching skills of Perl, and wonders how much better he’ll be at scavenging useful information with Perl 6 rules.

As a strong believer in ecology, Wheelbarrow also loves CPAN, and hopes that Perl 6’s version of CPAN will be even better at helping him reduce, reuse, and recycle.

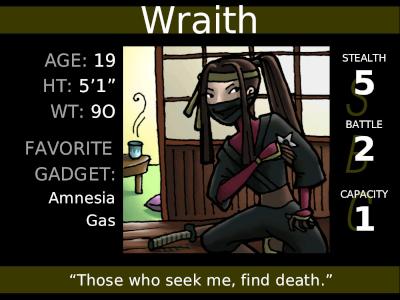

Wraith has trained herself to be good at hiding. She’s particularly good at information hiding and various forms of encapsulation.

Wraith also loves all the crazy new Perl 6 operators, especially the ones that will allow her to express parallel operations implicitly. She is willing to train herself in their skillful use because she values efficiency of expression. Why toss a single throwing star when you can throw eight at once?

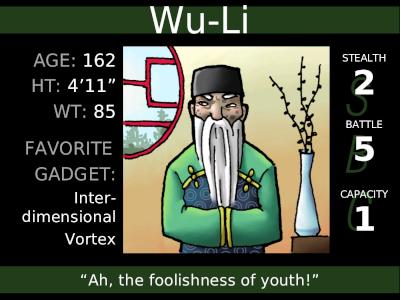

Wu-Li is the old guy who is interested in Unicode, and is looking forward to Perl 6’s built-in support for efficient and ubiquitous Unicode processing. Wu-Li likes to think about the various positive and negative aspects of various strange philosophies, whether Eastern, Western, Northern, Southern, or somewhere in-between.

Wu-Li isn’t actually Chinese. He only thinks he’s Chinese because when he was young his parents told him that every third child born into the world was Chinese, and he was a third child.

As a foreteller of the future, Wu-Li is the only person who knows when Perl 6 is coming out, and I’m not telling. Er, he’s not telling.

Wu-Li is also known for giving peculiar speeches from time to time.

And finally we come to Mr. X. I don’t know much about Mr. X, because nobody knows anything about Mr. X except Mr. X himself. We can only guess.

Mr. X seems to be highly placed in his organization, because all his information is of high quality, and of strategic value. Mr. X seems to believe in clean interfaces, with no extraneous information. He’s a master of the deaddrop, and other forms of message passing. He seems to understand Perl 6’s concept of delegation, so he’s probably in management. Perhaps he’s the CIO. Or maybe he’s the CFO’s assistant. Who knows?

In any event, he may be someone with some decision-making power, but he can’t afford to compromise his position by being overtly in favor of open source. At least, not yet. Nevertheless, he may be the most important player in the eventual success of open source. Mr. X is future-oriented, and as enigmatic as the future itself. We sincerely hope he turns out to be a nice person.

That’s our organization in a nutshell. We sincerely hope you’ll join up. Unfortunately, if you don’t join, we’ll have to liquidate you.

Well, enough of that. If this were an ordinary State of the Onion speech, I would now go into my standard spiel about how diverse the open source community is and how it’s such a great thing that we can pool our various strengths and produce something greater than any of us can do alone. And if this conference were still in California, I might say it again anyway, since diversity in California is not just encouraged, it’s actually required, culturally speaking. Californians have gotten to the point of being completely intolerant of non-diversity. But we’re not in California, so let’s just assume I said all that again and go on to something else.

I’d like to leave you with one thought, along with all these pretty pictures.

As I was thinking about the intelligence community and its recent obvious failures, it kinda put a new spin onto the phrase, “Information wants to be free,” or my own version of it, which is that “Information wants to be useful.”

We often think that intelligence failures are caused by having too little information. But often, in retrospect, we find that the problem is too much information, and that in fact, we had the data available to us, if only it had been analyzed correctly.

So I’m just wondering if we’re getting ourselves into a similar situation with open source software. More software is not always better software. Google notwithstanding, I think it’s actually getting harder and harder over time to find that nugget you’re looking for. This process of re-inventing the wheel makes better wheels, but we’re running the risk of getting buried under a lot of half-built wheels.

And there are two take-home lessons from that. The first is that, as an open source author, you should be quick to try to make someone else’s half-built wheel better, and slow to try to make your own. We’re making progress in this realm in the Perl community, but I don’t think any open source community ever gets good enough at harmonizing the dissimilar interests that sometimes lead to project forks. We can always improve there.

The second take-home lesson is this. Pity your poor intelligence analyst back at headquarters. He’s not all that intelligent, after all. The intelligence of the intelligence community is distributed, and it’s often the Tinas and the Wheelbarrows of the world that know when they’ve got a piece of hot information. But somehow that meta-information gets lost on transmission back to headquarters.

So my plea to all you agents out there today is to use your own initiative in figuring out which things to bother us with, and which things to work out for yourself. You’re smart, and the worst that can happen is that we tell you that you’ve wasted some effort. Just think of it as a kind of commit and rollback mechanism. Recent studies in multithreading show that hard locks do not scale as well as Software Transactional Memory, which is just such a commit/rollback mechanism.

Look around you. We are a multithreaded organization, so the same is true socially. It’s easy to get offended or discouraged when a rollback happens, but just don’t. The whole community will function more efficiently that way.

But if you get rolled back on something you know is important, just keep pushing. Those of us back at headquarters try to stay flexible and open-minded, but we don’t always succeed. So keep that good intel coming in, because good analysts can change their minds occasionally, too. At least, that’s what I think this week, and this year.

This talk will self-destruct in five seconds. Thank you all for listening.

Tags

Feedback

Something wrong with this article? Help us out by opening an issue or pull request on GitHub